The

first Corridor of Time exhibit, marine life during the

Cretaceous featuring the restored Cooperstown mosasaur skeleton,

opens at the North Dakota Heritage Center |

||||||||||||||||

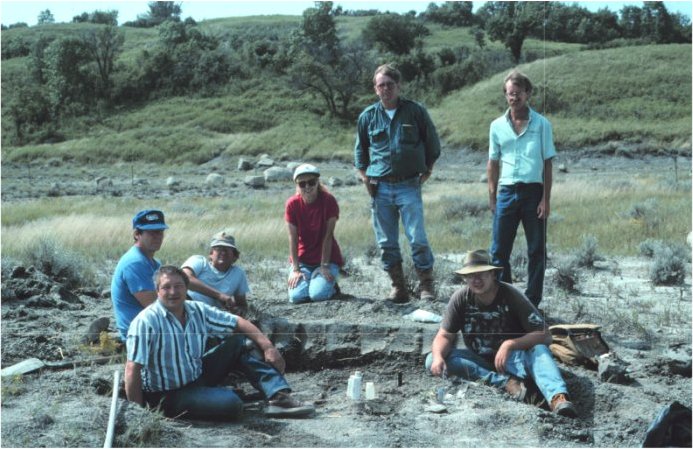

On

Saturday, July 8, a private reception, sponsored by the State Historical

Society of North Dakota, State Historical Society of North Dakota

Foundation, and North Dakota Geological Survey, was held at the North

Dakota Heritage Center to inaugurate the new marine Cretaceous exhibit

(Fig. 1) and recognize and thank donors of fossil specimens and funds

for contributions that made the exhibit possible. Presentations

were given by Sam Wegner, superintendent of the State Historical

Society of North Dakota, Barb Lang, president of the State Historical

Society Foundation Board, John Bluemle, State Geologist of North

Dakota, Heidi Heitkamp, North Dakota Attorney General, and John Hoganson,

North Dakota Geological Survey paleontologist. Over 480 people

attended the reception. An additional 1,050 people participated

in events at the public grand opening of the exhibit on Sunday, July

9. The public opening, organized by the State Historical Society,

included several children's activities, refreshments, and a slide

presentation by John Hoganson about the collection and restoration

of the Cooperstown mosasaur specimen.

|

||||||||||||||||

The marine Cretaceous exhibit (Fig. 1) is the first of several displays planned for the Corridor of Time, located at the entrance to the main exhibit gallery in the Heritage Center. The Corridor of Time will trace the geological development of the State of North Dakota and history of life in North Dakota as known from the fossil record. This story will begin about 550 million years ago during the Cambrian Period and end about 10,000 years ago at the end of the last Ice Age when humans first appeared in North Dakota. The Corridor of Time will consist of several exhibits that will interpret the geological framework and dominant life forms that inhabited North Dakota at different times in the geologic past. |

||||||||||||||||

The Corridor of Time will provide an introduction to the remainder of the Heritage Center museum exhibits, which are devoted to the historical development of North Dakota from the time of the first appearance of humans in the state up to the present. Briefly, in addition to the marine Cretaceous exhibit, the following other exhibits are currently being developed for the Corridor of Time. |

||||||||||||||||

North Dakota's Primordial Oceans During

most of time from about 550 million years ago until about 90 million

years ago, shallow oceans covered North Dakota. No rocks

from this time are exposed at the surface of the earth in North

Dakota, so information is sketchy about this long period in North

Dakota's geological history. Geological and paleontological

information from this time is obtained by analysis of cylinders

of rocks, called cores, which are brought to the surface during

exploration for oil and gas by the petroleum companies. These

cores commonly exhibit features in the rocks that provide information

about the geological conditions when the rock started forming in

the bottom of the ocean. Some core samples contain fossils

of animals that lived in those oceans. This exhibit will

contain many cores that provide a record of the many oceanic, climatic,

and life form changes through millions of years of this most ancient

time in North Dakota's history. |

||||||||||||||||

This display will be concerned with life that inhabited a huge delta that occupied western North Dakota at the end of the Cretaceous Period about 65 million years ago. This story is based on rocks and fossils of the Hell Creek Formation exposed in south-central and southwestern North Dakota. Fossils of some of the largest animals ever to live in North Dakota, dinosaurs including Triceratops (Fig. 2), T. rex, hadrosaurs, and dromaeosaurs, will be featured. Fossils of other members of the community that lived with the dinosaurs, including crocodiles, champsosaurs, turtles, mammals, freshwater snails and clams, and plants will be included. |

||||||||||||||||

|

The North Dakota Everglades

The North Dakota everglades exhibit will portray the geology of North Dakota and the prehistoric life that lived in North Dakota from about 65 to 50 million years ago. During this period, western North Dakota was mostly a lowland containing huge swamps and forests with a subtropical to tropical climate, not too different than areas of south Florida today. The last of the dinosaurs had become extinct before this time and the dominant life forms in North Dakota were crocodiles, alligators, champsosaurs (Fig. 3A), and turtles (Fig. 3B), as indicated by fossils found in rocks deposited during the Paleocene Epoch. These rocks are extensively exposed in most of the badland areas of western North Dakota. Fossils of other animals, such as mammals, clams, snails, and exotic plants, including redwood (Fig. 3C), bald cypress, ginkgo, and magnolia illustrate the diversity of life in North Dakota at this time.

North Dakota's Last Sea About 60 million years ago the last ocean to cover North Dakota, the Cannonball Sea, retreated from the upper mid-continent. Fossils found in the rocks deposited in that sea, primarily exposed in south-central North Dakota, will be featured in this exhibit. The remains of many kinds of animals that inhabited these shallow water marine environments have been found and will be exhibited including: teeth of sharks, rays, ratfish, other fish; shells of crabs, lobster, snails and clams; and North Dakota's state fossil, Teredo-bored petrified wood. The North Dakota Savanna The humid, subtropical, swampy environment reflected by rocks and fossils in the North Dakota everglades exhibit gradually changed to drier, temperate conditions. Savanna habitats were established in North Dakota by at least 35 million years ago. North Dakota's landscape was rather featureless and rivers and streams meandered across the savanna. Little is known about plant life in North Dakota during this time because few plant fossils have been found. Woody vegetation probably grew in the open savanna areas and forests were established along the watercourses. Herds of exotic mammals roamed North Dakota indicated by abundant fossils found in the Chadron and Brule Formations in areas of western North Dakota. The remains of elephant-size titanotheres, rhinoceroses, camels, three-toed horses, sheep-like oreodonts, mongoose-like animals, saber-toothed cats, rabbits, and mice will be included in the exhibit. Tortoise, lizard, and fish fossils will also be displayed.

|

||||||||||||||||

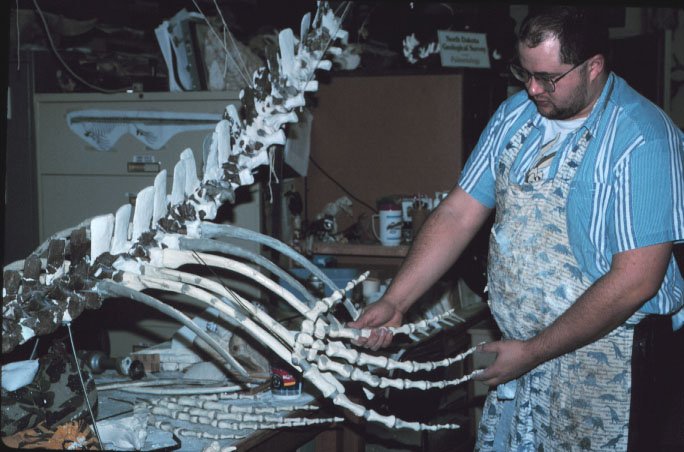

During the latter part of the Cretaceous Period, from about 90 million to about 65 million years ago, North Dakota was mostly covered by epicontinental seas that occupied the Western Interior Seaway (Fig. 5). At times, these seas covered the entire North American mid-continent and connected the Gulf of Mexico with the Arctic Ocean. The new marine Cretaceous exhibit is about that time in North Dakota's geologic past. This exhibit features the restored skeleton of a 23-foot-long mosasaur. Mosasaurs were large marine lizards and the main predators in the seas. Their bodies were streamlined and they possessed flippers. They propelled themselves through the water by lateral movements of their body and tail. The flippers were mostly used for steering. Their heads were huge and equipped with large, conical teeth. Although they became extinct at the end of the Cretaceous, like the last of the dinosaurs, mosasaurs were not dinosaurs. They are categorized as varanid lizards and are related to the monitor lizards, such as the Komodo dragon that lives in Indonesia today. |

||||||||||||||||

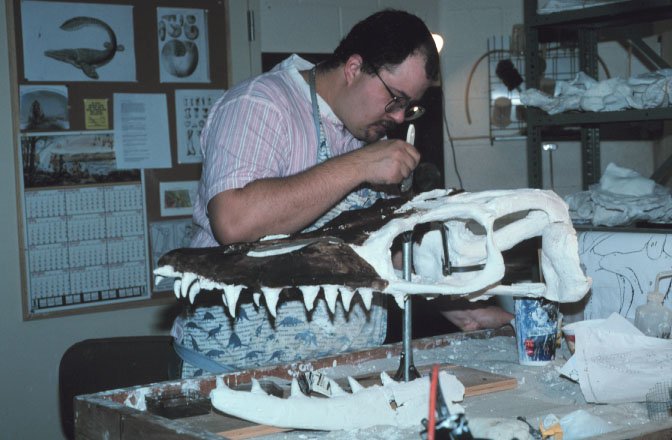

The mosasaur skeleton on

display was discovered by Mike Hanson and Dennis Halvorson of Cooperstown. It was weathering out

of the Pierre Shale in the Sheyenne River valley on Beverly and Orville

Tranby's property near Cooperstown (Fig. 6). The Tranby's and Bev's

sisters, Gloria Thompson, Jacqueline Evenson, and Susan Wilhelm, donated

the specimen to the State Fossil Collection for study and display at

the North Dakota Heritage Center. This mosasaur is identified as being

in the

group of mosasaurs called Plioplatecarpus. Because of its huge size

(the skull is three feet long; Fig. 7) and structure of bones in the skull and

post-cranial skeleton, it has been determined that this specimen represents a

new species of Plioplatecarpus not found anywhere

else in the world. Because of the scientific importance of this fossil,

molds of the skull bones were made and casts of these bones were assembled to

the form the skull that is attached to the displayed three-dimensional skeleton

(Fig. 8). The real skull bones are also on display but are protected under

a plexiglass cube.

Included in this exhibit are fossils of other marine animals that lived with the mosasaur including remains of sharks, other fish, birds, corals, crabs, snails, and clams (see summer/fall 1996 NDGS Newsletter (vol. 23, no. 2 & 3)). Many of these fossils were found on the Jergen Soma property and the Soma family has donated them to the State Fossil Collection.

Fossils from other marine Cretaceous sites are also included in the exhibit. Particularly impressive are the beautifully preserved ammonites (Fig. 9) found in the Fox Hills Formation near Linton, some of which were donated by Pat Liska and Duane Robey. A large sandstone block, containing in situ clams (Panopia) collected from the Fox Hills Formation and donated by J. Mark Erickson, is displayed. Many extraordinarily preserved clam, snail, and shark tooth fossils, from an important Logan County Fox Hills site, are included. The sand covering the "ocean floor" part of the exhibit is 68-million-year-old beach sand from this Logan County site. Fossils in the marine Cretaceous exhibit show that the epicontinental seas that covered North Dakota during the Late Cretaceous were shallow, warm-water habitats that were teaming with life. We were fortunate to be able to commission David Miller, an artist specializing in prehistoric life habitat reconstructions from Bellingham, Washington, to create an image of life in the Pierre Sea 75 million years ago based on fossils from the Cooperstown fossil site. |

||||||||||||||||

The painting features the

predatory mosasaur Plioplatecarpus attacking a large, flightless, diving

seabird called Hesperornis (Fig. 10). Hesperornis, also a predator

that possessed small, sharp, pointed teeth, has just captured

a salmon-like fish (Enchodus). Other fish, including a large shark

similar to the living sand-tiger shark, cruise this shallow water

ocean. Invertebrate animals, snails and clams, reside on the ocean

floor. In the background, a decaying carcass of a mosasaur has settled

to the bottom. This carcass is being scavenged by a school of small dogfish

sharks (Squalus). This was the fate of the Cooperstown mosasaur

when it died. Evidence for this is the thousands of small dogfish shark

teeth found with the Cooperstown mosasaur skeleton and gnaw marks created by

dogfish sharks noted on some of the mosasaur bones. This painting, depicting

a moment of time in North Dakota's geologic past, was enlarged to a 8-foot-by-12-foot

mural and is mounted on the wall behind the suspended mosasaur skeleton. More

than 17,000 people viewed the marine Cretaceous exhibit in July, about 6,000

more visitors to the Heritage Center

than the previous July. This dramatic increase in visitation is, at least

in part, attributed to the new exhibit. These kinds of prehistoric life

exhibits, although popular, are costly to produce. For example, it took

Johnathan Campbell, NDGS fossil preparator, about two years to restore the mosasaur

skeleton (Fig. 11). The marine Cretaceous exhibit results from a cooperative

effort between the North Dakota Geological Survey and State Historical Society

of North Dakota with time contributed by numerous

volunteers. Over $14,000 was raised from private sources to complete the

exhibit. Over $100,000, of the $500,000 needed to finish the Corridor

of Time, has been raised so far. Please feel free to contact me if you are

interested

in helping finance the Corridor of Time project.

On behalf of the North Dakota Geological Survey, I would again like to thank the people and organizations that donated fossil specimens and contributed funds, which made this exhibit possible. |

||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||