Mosasaurs, Sharks, and Other Marine Creatures from the Cooperstown Pierre Shale Site

by

|

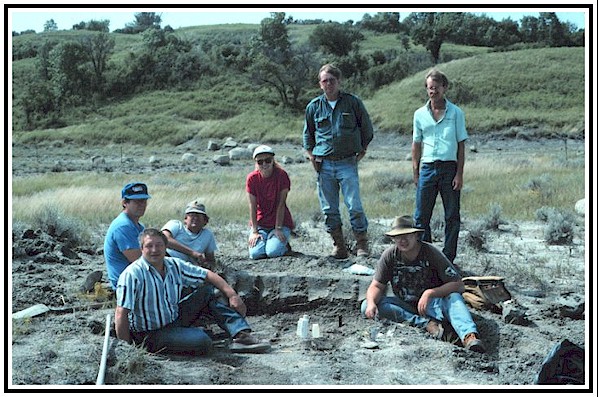

| Figure 1 - Mike Hanson and Dennis Halvorson at the Cooperstown Site. Note "Indian Mounds" in the background exposing the fossil-bearing Pierre Shale. |

|

Figure

2 - National Geographic Society map of the

Western Interior Seaway showing the location of the Cooperstown

site. |

|

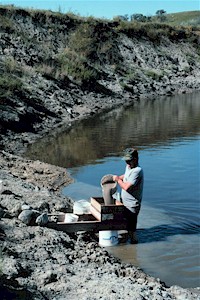

| Figure 3 - Mike Hanson screen washing Gregory Member claystone for fossils along the Sheyenne River. |

| Figures

4A-4Q. Fossils of invertebrate animals recovered from the Gregory Member of the Pierre Shale. |

|||

|

4B. Brachiopod (Lingula) height 3 mm |

4C. Coral (Micrabacia) width 4 mm |

4D. Coral height 11 mm |

4E. Clam (Nucula) width 17 mm |

4F. Clam (Nemodon?) width 3 mm |

4G. Snail (Margaritella) width 8 mm |

4H. Snail (Trachytriton) height 20 mm |

4I. Snail height 12 mm |

4J. Cephalopod (Baculites gregoryensis, adult) length 55 mm |

4L. Cephalopod (Didymoceras) height 27 mm |

4M. Cephalopod (Solenoceras mortoni) height 19 mm |

| 4K. Cephalopod (Baculites gregoryensis, juvenile) length 11 mm |

|||

4N. Shrimp (Callianassa, claw) length 20 mm |

4O. Starfish (single plate) height 7 mm |

4P. Sea Urchin (Eurysalenia) width 7 mm |

4Q. Sea Urchin (Eurysalenia spine) height 4 mm |

|

| Figure

5 - Smithsonian reconstruction of a Cretaceous age seafloor with

many of the animals represented by fossils at the Cooperstown site.

|

Figure

6A-6J - Fossils of vertebrate animals recovered from the DeGrey Member of the Pierre Shale. |

|||

6A. Shark tooth (Squalicorax) width 20 mm |

6B. Shark tooth (Pseudocorax) width 10 mm |

6C. Shark tooth (Cretolamna) height24 mm |

6D. Shark tooth (Carcharias) height 10 mm |

6E. Shark tooth (Squalus) width 6 mm |

6F. Shark placoid scale (Squalus) width 1 mm |

6G. Salmon like fish tooth (Enchodus) height 4 mm |

6J.Coprolite, fossilized excrement length 31 mm |

6I.

Tarso-metatarsal of a Hesperornis bird length 90 mm 6I.

Tarso-metatarsal of a Hesperornis bird length 90 mm6H. Diagram of a Hesperornis bird skeleton (from Carroll, 1988) height 2 m |

|||

7A. Diagram of a mosasaur skeleton similar to the ones found at the Cooperstown site (From Russell, 1967). |

||

|

7C. Tooth of excavated Plioplatecarpus height 70 mm |

7D. Shoulder blade of excavated Plioplatecarpus width 308 mm |

|

Figure

8.

Tips of the lower jaws of the mosasaur, Plioplatecarpus, being excavated by Johnathan

Campbell. |

We have begun preparation and study of the fossils from this important Pierre Shale site and have presented some preliminary results of our findings (Figure 13 and see additional readings below). These fossils provide a glimpse of what life was like in the shallow, subtropical sea that covered the Cooperstown area. It was obviously teaming with life reflected by the variety of fossils found at the site. We expect to learn more as work continues on the fossils.

|

Figure

9. Dennis

Halvorson, Johnathan

Campbell, Mike Hanson and Seth Hanson excavating the Plioplatecarpus skeleton. |

|

| Figure 10. John Hoganson mapping the position of the bones at the Plioplatecarpus excavation. |

|

| Figure

11. Applying a plaster cast on some of the Plioplatecarpus bones. (Left to right) Johnathan Campbell, John Hoganson and Mike Hanson. |

|

| Figure 12. Orville Tranby lifting one of the large plaster casts containing Plioplatecarpus bones. Bev. Tranby in foreground. |

|

| Figure

13.

Johnathan Campbell restoring one of the

Plioplatecarpus jaws in the NDGS paleontology laboratory at the North Dakota Heritage Center. |

One of the intriguing questions is how the mosasaurs at this site may have died. Is it possible that these animals all died at about the same time, suffocated by volcanic ash? The mosasaur bones are found in the Pierre Shale associated with layers of bentonite, altered volcanic ash. Did volcanic eruptions far to the west create enough air fall ash in North Dakota to decimate the mosasaur population in the Pierre Sea? We are also interested in how these animals interacted as a community. During preliminary cleaning of some of the mosasaur bones, teeth (Figure 6E ) and placoid scales (Figure 6F) of dogfish sharks were found with the mosasaur bones. Sharks often loose their teeth while feeding. Could it be that dogfish sharks scavenged this mosasaur carcass? Or, perhaps the mosasaur preyed on the dogfish sharks and these teeth and scales are undigested residues. Hopefully we will be able to answer some of these questions.

Mike, Dennis, Verla, and

I would like to thank Orville and Beverly Tranby and family and the

Tim Soma family for allowing us to collect and study fossils from their

property (Figure 14). These fossils are currently in our laboratory

at the North Dakota Heritage Center in Bismarck for curation and study.

Most of the fossils, however, will eventually be exhibited at the Griggs

County Museum in Cooperstown. We believe that the Plioplatecarpus

mosasaur skeleton is complete enough to restore as a three dimensional

skeletal mount exhibit. Because of the importance of this specimen,

Orville and Beverly and Beverly's sisters, Mrs. Gloria Thompson, Mrs.

Jacqueline Evenson, and Mrs. Susan Wilhelm have decided to donate this

fossil to the North Dakota State Fossil Collection for study and exhibit

at the Heritage Center. We thank them forthis donation as it will

be an educational and a popular exhibit that will be viewed by many.

Chris Dill, State Historical Society of North Dakota and Museum Director

of the Heritage Center, enthusiastically supports a mosasaur exhibit

and has given us the authorization to proceed with the exhibit

plans. A fossil restoration project such as this is a major and

expensive undertaking and will be accomplished only through private

donations. If any of you are interesting in financially supporting the

restoration of the Cooperstown mosasaur for exhibit at the Heritage

Center please contact me.

Hoganson, J. W., Hanson, Michael, Halvorson, D. L., and Halvorson, Verla, 1996, Stratigraphy and paleontology of the Pierre Shale (Campanian), Cooperstown site, Griggs County, North Dakota: Proceedings of the North Dakota Academy of Science, v. 50, p. 34.

Hoganson, J. W., Hanson, Michael, Halvorson, D. L., and Halvorson, Verla, 1996, Mosasaur remains and associated fossils from the DeGrey Member (Campanian) of the Pierre Shale, Cooperstown site, Griggs County, east central North Dakota: Geological Society of America, Rocky Mountain Section, abstracts with programs, v. 28, no. 4, p. 11-12.;

Johnathan Campbell, and Scott Tranby at the mosasaur excavation site.

|

North Dakota Geological Survey Home Page | |

| Update: 31.08.04 jal |